Methodist Beginnings

The Illinois Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church established the Illinois Conference Female Academy in Jacksonville in 1846. The institution provided “for the intellectual and moral education” of women in the interests of government and society. The school catered to teachers, benevolent workers and missionary workers. The early founders were comprised of devout and erudite clergymen, Peter Cartwright and Peter Akers, as well as several of Jacksonville’s prominent men. Along with the Conference’s Committee on Education, these men solicited funds, located teachers, selected five acres on East State Street for purchase to erect a building and chose the first president: James Frazier Jaquess, a Methodist minister educated at what is now DePauw University in Indiana.

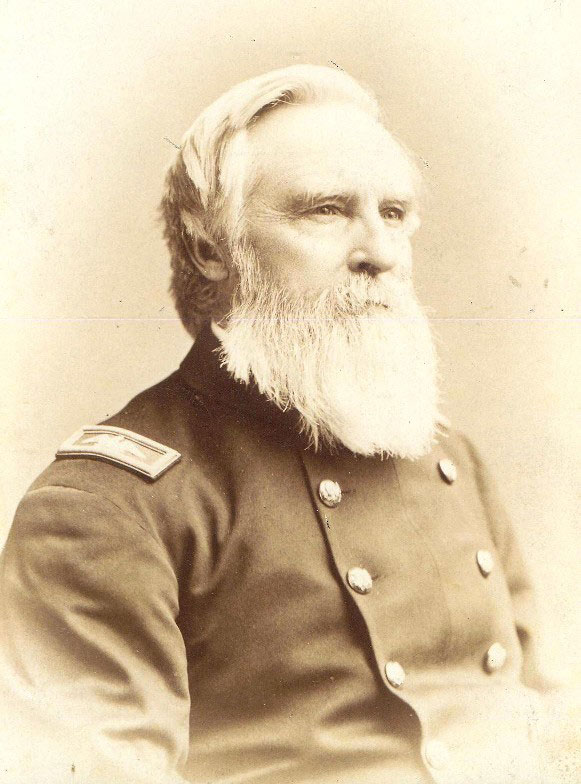

James Jaquess

The first classes opened in the basement of the East Charge MEC (now Centenary United Methodist Church) in 1847 with a modest enrollment of 117, divided into preparatory and academic departments. In addition to soliciting funds and students, James Jaquess taught chemistry.

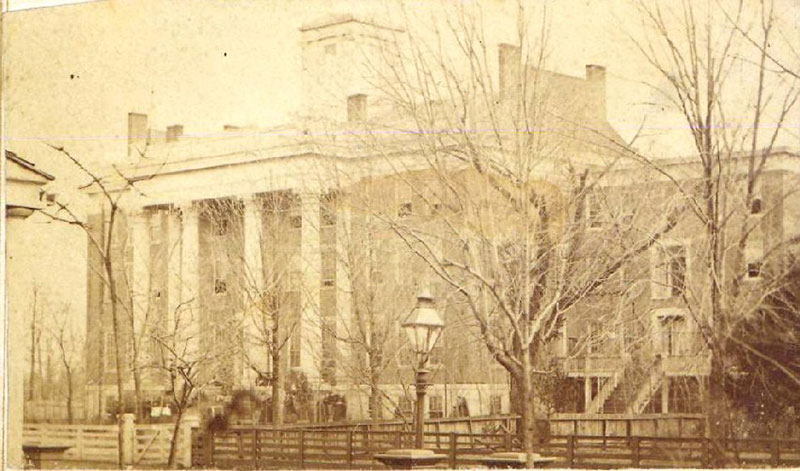

The first building, Main, was completed in 1850, which provided classroom space along with housing for Jaquess and the students. Before Main, out-of-town students lived with local Methodist families.

In 1854, Jaquess discontinued the primary department to engage students in more challenging and expanded curriculum that included economics, political discourses and additional sciences. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the College experienced an increased enrollment requiring wing additions to Main. Even through financial setbacks, specifically the Civil War and three fires occurring over ten years to Main, the school flourished and continued to attract students. The first literary societies, Belles Lettres and Phi Nu, were organized in the 1850s. Two presidents re-chartered the academy sequentially under new names: Illinois Conference Female College and Illinois Female College.

IWC and Continued Expansion

In 1893, the College’s fortune changed when the trustees chose Dr. Joseph Harker as the seventh president. Harker changed the College’s name in 1899 to Illinois Woman’s College (IWC), envisioning a standard college with an enhanced college campus. With successful capital campaigns conducted by the Methodist Episcopal Church and Dr. Harker, a large endowment was established and in 1909, the College granted baccalaureate degrees. In 1913, as evidence of the improved curriculum elevating the College to a higher rank of academics, the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools granted accreditation. In 1920, the Association of American Universities placed IWC on the “accepted” list and a year later, the College became a corporate member of the American Association of University Women. During Harker’s administration, the College added the Fine Arts Building, Harker Residence Hall, a powerhouse, and Hardtner Gymnasium and Pool.

Joseph R. Harker

Joseph R. Harker was the college’s longest-serving president and one of its most successful. His upbringing was difficult. Born in poverty, his formal education ended at the age of ten. He worked in the coal mines outside his native Durham, England, and then after his family immigrated to this country, in southern Illinois. Former Board of Trustees chairman Allen Croessmann ’68 recounts the early years of Harker — his rise from coal miner to college president — in an article published in Illinois Heritage magazine.

James MacMurray

Following Harker’s retirement in 1925, the next president, Dr. Clarence McClelland, wanted to continue Harker’s plan. McClelland, previously a successful president of Drew Seminary for Young Women in New York, continued the work of Dr. Harker, following his vision of an expanded curriculum and campus. Expansion was more easily accomplished with the significant financial contribution and support of trustee board chairman, James MacMurray, a wealthy, prominent Chicago businessman and former Illinois state senator. In 1926, the two Scotsmen launched a twenty-year campus expansion, adding a science building, MacMurray Science Hall, and dining hall, McClelland Dining Hall, and three residence halls: Harker, Jane, Rutledge, and Katherine. In recognition of MacMurray’s generosity, IWC’s name became MacMurray College for Women in 1930. Before McClelland retired in 1952, the College had gained a new chapel and library at the benevolence of Henry and Annie Merner Pfeiffer, and purchased a building for a college theatre which also housed a radio show.

MacMurray Legacy

In the 1930s McClelland relaxed many of the rules governing academic and social life. During World War II, student activities supported the war effort but social functions, such as dances and theatre performances, continued as much as possible. In 1946, the College celebrated its centennial anniversary with week-long activities.

McClelland’s successor, Louis Norris, a strong proponent of MacMurray remaining a women’s college, realized that a new day had dawned. A decline in the birth rate during the Great Depression, coupled with the economic stress on separate colleges for men and women and the acceleration of a trend that had begun decades earlier toward coeducation nationwide, caused MacMurray to reevaluate its position. In 1955 the Board of Trustees, on the motion of Milburn Peter Akers, grandson of Founder Peter Akers, voted to establish a MacMurray College for Men that would exist alongside MacMurray College for Women. The school newspaper, The Greetings, broke the news: “It’s a Boy! Sally Mac Gets a Kid Brother.” The first full class of men entered in the fall of 1957.

The decision to admit men stemmed in large part from a desire to take advantage of the great number of Baby Boomers who would be entering college in the 1960s. During the 50’s and 60’s, new residence halls were built on the South Campus to accommodate men: Kendall, Blackstock, Norris and Michalson. The two coordinate colleges joined in 1969 to become the coeducational MacMurray College.

Enrollment at the College grew from some 500 at the beginning of the Norris presidency to over 1000 during the later years of President Gordon Michalson, who succeeded Norris, and the first years of President John Wittich. This was the high-water mark for the institution in terms of enrollment. Michalson believed that the curriculum needed to be simplified and refocused. Some 200 courses were dropped from the catalogue, some of which had not been taught in years. What became known as “The MacMurray Plan” was instituted with its unwavering emphasis on the liberal arts.

MacMurray experienced much of the turbulence of the 1960s and 1970s as did other college campuses across the country with students voicing concerns over Civil Rights, the Vietnam War and individual freedoms. The new Percy Julian Chemistry building and Campus Center for students were built, as were additional men’s residence halls. The last major new construction on campus occurred during the Lawrence Bryan administration: The Putnam Center for the Arts and the Springer Center for Music on the site of the razed Main and Harker Halls. It was also during the Bryan regime that MacMurray celebrated its sesquicentennial.

Financial problems, always the bane of MacMurray’s existence, were never absent. Enrollment had grown, but it was still lower than it needed to be. The infrastructure had grown and an excellent faculty had to be fairly compensated. Increased aid to public institutions was disadvantageous to private institutions. There was also the advent of two-year community colleges, a new competitor for students.

During the 1980s the College’s financial condition became dire. New President Edward Mitchell stabilized the situation in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but President Colleen Hester, the school’s first female president, needed to do it again during her tenure from 2007 to 2015. Budgets were balanced, indebtedness to banks was reduced, and the balance sheet improved. Yet after her departure, the situation deteriorated quickly.

New President Mark Tierno achieved positive press nationally for the institution with his cross-country “MacNation” tour where he met hundreds of alumni and friends of the College. To fund some long-deferred campus maintenance, the Board of Trustees authorized a significant borrowing, but the real problem was that the College had to offer more in financial assistance than it had in the past to keep up with the competition for quality students. That might have worked had the enrollment increased but it did not. Enrollment hovered in the low 500s. The result was that net revenue declined and significant budget deficits were incurred. President Tierno left in 2019, and his successor, the college provost and vice president of academic affairs, Dr. Beverly E. Rodgers, threw herself into the effort to save the College, but it was too late. In addition, the 2020 worldwide Covid pandemic impacted student enrollment and campus residency. The capital required to keep the institution going was not forthcoming and In March 2020, the Board of Trustees voted to close the 174-year-old institution.

While the College that had educated so many women and men across seven generations had closed its doors, its sprit lives on through its devoted alums and through the work of the newly established MacMurray Foundation & Alumni Association. MacMurray College’s values of knowledge, faith, service, wisdom, duty, and loyalty will continue.

Further Reading

Burnette, Patricia B. James B. Jaquess: Scholar, Soldier and Private Agent for President Lincoln, 2013.

Harker, Joseph R. Eventide Memories, 1931.

Hendrickson, Walter B. Forward in the Second Century of MacMurray College: A History of 125 Years, 1972.

MacMurray, James E. The Man from Missouri, 1943.

Watters, Mary. The First Hundred Years of MacMurray College, 1947.

The Tartan

In honor of James MacMurray, the College’s namesake and one of its most generous benefactors, MacMurray College was proud to honor his Scottish heritage. The excerpts below are from The Clans and Tartans of Scotland by Robert Bain and outline the history of the family whose tartan MacMurray displays.

MURRAY

Crest Badge:

A mermaid holding in her dexter hand a mirror, and in the sinister a comb all proper. The crest shown is that of the ancient families who lay claim to the chiefship of Murray.

Motto:

Tout Prêt (Quite Ready)

Gaelic Name:

MacMhuirich

This powerful clan had its origin in one of the ancient tribes of the Province of Moray. The clan name is found in many districts of Scotland, and the principal family is said to be descended from Freskin, who received lands in Moray from David I. His grandson, William, because of extensive possessions in Moray is described as de Moravia. He acquired the lands of Bothwell and others in the South of Scotland, and several of his sons founded other houses, including the Murrays of Tullibardine. He died in 1226 and his son, Sir Walter, was the first described as of Bothwell. Sir Walter’s son, Sir William de Moravia, dominus de Bothwell, died without issue in 1293 and was succeeded by his brother, Sir Andrew, who was the celebrated patriot and staunch supporter of Sir William Wallace. His son, also Sir Andrew, with Wallace, sent the famous letter dated October 11, 1297, to the Mayors of Lubeck and of Hamburg informing them that the Scottish ports were again open for trade. He was Regent of Scotland after the death of Robert the Bruce and died in 1338.

Sir William de Moravia acquired the lands of Tullibardine in Perthshire in 1282 through his marriage with a daughter of Malise, seneschal of Strathearn. Sir William Murray of Tullibardine, who succeeded in 1446, had seventeen sons, many of whom founded prominent families of Murray. Sir John, 12th of Tullibardine, was created Lord Murray in 1604 and Earl of Tullibardine in 1606. William, 2nd Earl of Tullibardine, claimed the Earldom of Atholl by right of his wife but died before the patent was granted. His son, John, however, obtained the title of Earl of Atholl in 1629 and became the first Earl of the Murray branch.

MURRAY OF TULLIBARDINE TARTAN

ORIGIN OF NAME: Place-name, Morayshire.

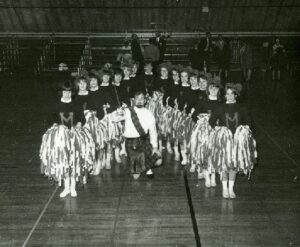

Mac the Highlander

The story of Mac the Highlander began with the College’s eighth president, Dr. Clarence McClelland, and James MacMurray, a wealthy and prominent Chicago businessman and former Illinois state senator. In 1926, the two men, both having Scottish ancestry, worked together to launch a twenty-year campaign that would expand the campus of what was known then as the Illinois Woman’s College. By 1930, the College had added a science building, dining hall and a residence hall as well as changing its name to the MacMurray College for Women in honor of Sen. MacMurray’s generosity.

After the MacMurray College for Men was established and the first class of men arrived in 1957, the freshmen were given the opportunity to choose the College’s mascot and seal. Sticking to MacMurray’s Scottish heritage, the freshmen chose the Highlanders, the Tullibardine tartan plaid (the plaid of the Murray clan) and the Highland Times as the name for the school newspaper. The students were also given three different seals to choose from that were designed by Howard Sidman, an art professor at the College.

On July 26, 2017, our mascot officially embodied the spirit of MacMurray College and Mac the Highlander was introduced to alumni, students and friends of the College at the MacNation Return Celebration. Donned in the official MacMurray College tartan, Mac reminds us all to show our highlander spirit.